In Acts of Resistance, Artists and Scholars Digitally Reconstruct the Past

by Claire Voon

Hyperallergic / January 27,2016

In the past year alone, members of ISIS have marred cultural treasures in Iraq and Syria, taking sledgehammers and drills to statues at the Mosul Museum and delivering numerous blows to the ancient site of Palmyra, including its 1,800-year-old Arch of Triumph. With no end to such relentless destruction in sight — unfortunately, the savagery seems to only grow — the documentation and preservation of such artifacts of cultural heritage have become duties we must approach with a sense of urgency.

A number of projects that engage with existing and developing technologies have emerged in recent years to trace the histories of and even reconstruct destroyed objects. While many of these respond to cultural loss from human conflict, still others are concerned with ever-present sources and causes of erasure, from looting and illicit resales to weather and the passing of time. The Missing: Rebuilding the Past, a group exhibition at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, examines how artists use creative means to protest preventable loss. While many of the works on view engage specifically with ongoing destruction in conflict zones such as those in Iraq and Syria, the exhibit also explores projects focused on other regions that make us consider broader issues of cultural disappearance.

Perhaps the most well-known of reconstruction projects is one that responds directly to last February’s wrecking of the Mosul Museum: Material Speculation: ISIS, Iranian artist Morehshin Allahyari‘s ongoing series of 3D-printed objects. For almost a year, Allahyari has been researching a number of the museum’s destroyed artifacts — a painstaking effort, as relevant documents she found were often ill-translated, and the museum lacked sufficient funds to completely photograph its collection. On view as part of The Missing is an approximately one-foot-tall representation of a life-size sculpture of King Uthal, known as“the finest of all the sculptures unearthed in Hatra.” Inside the figurine resides a USB drive and memory card, onto which Allahyari loaded images, maps, videos, and PDF files representing all the research she found on the original object. The comprehensive and sturdy packaging stands in stark contrast to sculptures of a carving fragmented by ISIS bullet holes, cast in Iraq by Piers Secunda. While Secunda provides glaring evidence of the violence of war, Allahyari’s work looks towards the future; she is now seeking an institution that is able to preserve the data in a digital archive to provide open access to all this information so others may construct their own 3D models. To her, even that act would be one of resistance.

“The copy is actually making it more and more powerful every time you have a new 3D print of it,” Allahyari noted, speaking recently at a symposium on the future of digital archaeology held in conjunction with the exhibition. “Every time you save that file on your computer and keep it in a digital archive, you have somehow fought against the removal of that history.”

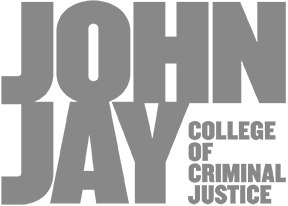

The Missing spotlights a number of existing online libraries attempting to safeguard heritage sites and objects. On display is a 3D rendering of an arch from the pulverized Temple of Bel — one example of the works the Million Image Database has created from the combined efforts of its volunteer photographers scattered across countries, including Syria, Iraq, Yemen, Afghanistan, and Egypt. These volunteers are armed with low-cost, easy-to-use cameras that capture stereoscopic images and automatically upload them to an open-source database. With the millions of 3D images amassed, the program intends to replicate full-scale models of at-risk artifacts. The Palmyra arch will be its first replication, landing this April in Times Square and Trafalgar Square. In a similar vein, albeit on a broader scale, the non-profit CyARK has been collecting 3D images of significant sites around the world — from the Brandenburg Gate to China’s Eastern Qing Tombs — some of which are featured in the gallery. Unlike most of the projects represented, this endeavor is one that anticipates threat, representing a broad concern to preserve history even in regions void of conflict.

One of the most poignant expressions of preservation in the exhibit actually comes from one of the smallest-scale projects that is currently seeking funding via GoFundMe. The in-progress digital 3D model of a theater in Palmyra was created by archaeologist Conan Parsons and is part of Palmyra Photogrammetry, his project that crowdsources unaltered holiday photos that feature the ancient ruins from different angles to eventually build a 3D model of the city. The image’s surface ripples as if painted with watercolors or as though the building were melting. This distortion stems from its incompletion, reminding of the large efforts required to properly reconstruct the missing: the image needs many, many more two-dimensional images to stitch together a precise 3D visual.

Such endeavors demonstrate how technologies — especially optic-based ones — are popular weapons for resistance, but as ISIS’s propaganda videos prove, those responsible for destruction also take full advantage of such tools. Through her collection of digital prints showing looted antiquities sold online, professor of art crime Erin Thompson presents the digital networks that support the disappearance of culture; at the same time, however, the pictures reveal how the very use of such systems also undermines these criminal acts. Taken by middlemen, these photographs were shared with potential buyers over social media networking sites from Facebook to Whatsapp, unintentionally providing crime investigators like Thompson with traces of the looted object’s history. Such images may eventually be matched with objects with falsified paperwork, with many offering evidence that their subjects were stolen: clear markers are items found in frames, from a carelessly left metal detector to a pack of cigarettes intended to show scale.

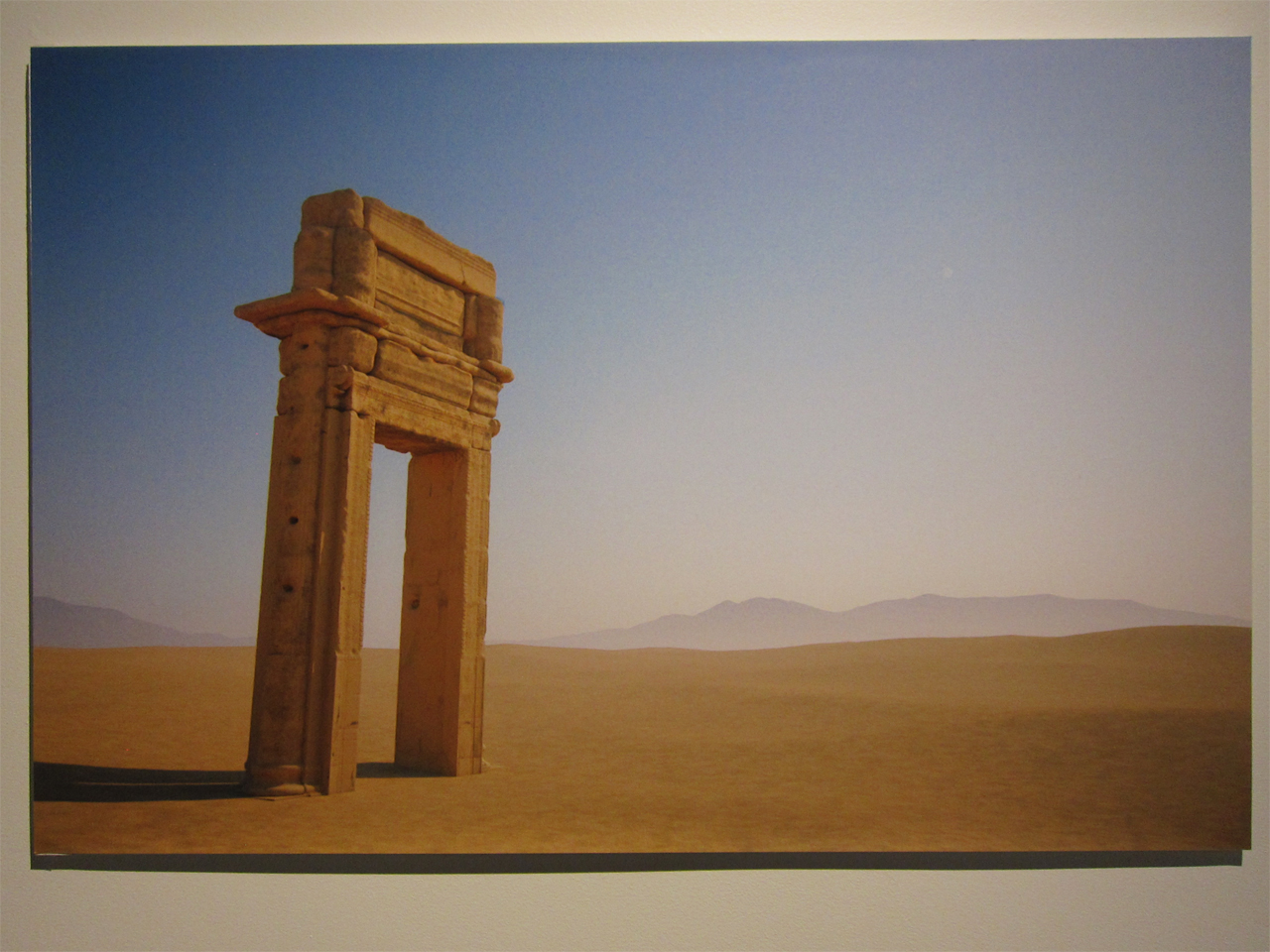

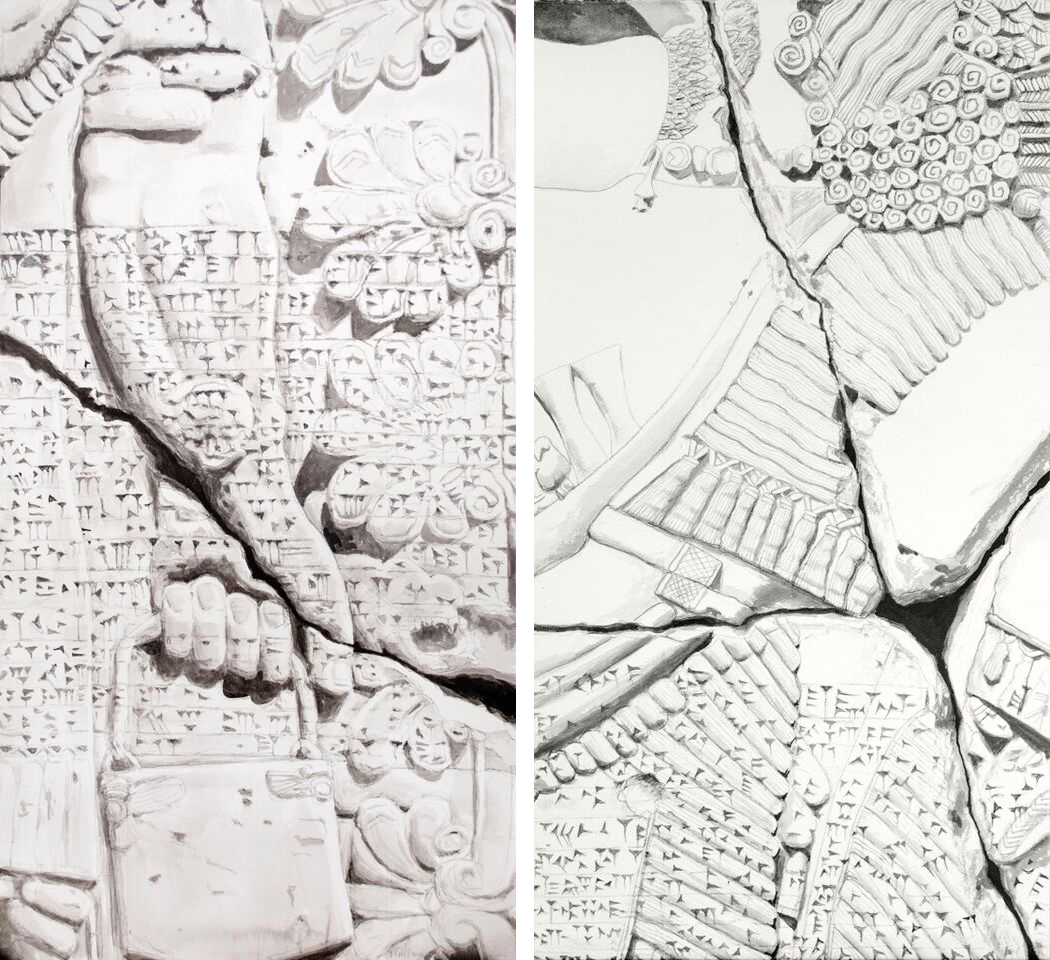

Looking to the past, a number of artworks engage with objects already preserved in museums to consider how we perceive relatively long-damaged works. Photographs by Dimitra Ermeidou, for instance, show ruined, ancient Greek reliefs at the National Archaeological Museum, while graphite drawings by Gail Rothschild zoom in on the cracks of Assyrian relief panels from the palace of Ashurnasirpal II at Nimrud, covered up in many museums but left in their scarred state at the Brooklyn Museum. Photographs by Chronis Spanos that pair unaltered and kaleidoscopic perspectives of the Acropolis and the Acropolis Museum make us revisit the highly familiar in foreign reconfigurations. Placed alongside homages to objects recently damaged or obliterated, these three works highlight ancient artworks we may overlook simply because of their established presence in museums. They make us reflect on the context in which they entered collections in the first place and how their wounds influence judgments of beauty and value.

Rothschild’s devoted illustrations to Nimrud are especially stirring when one considers that the world recently lost the original reliefs left in situ, destroyed when ISIS fighters barrel-bombed the ancient city last March. The virtual reality experience “Nimrud Rising” exemplifies the necessity of documenting such significant sites: the project began nearly two decades ago and now stands as one of the most elaborately reconstructed representations of a now-lost treasure. Although not directly included in The Missing, itsbeta version made its debut at the symposium, presented by its scientific director Donald Sanders of Learning Sites, Inc and its executive producer Peter Herdrich of the Antiquities Coalition. Users, wearing an Oculus Rift, may roam around the palace’s interior and exterior as seen during the Assyrian Empire, with every detail rendered with incredible precision. One may walk up to a wall and examine its reliefs, for instance, or observe the carvings of large Lamassu. Sanders and Herdrich intend for “Nimrud Rising” to be a teaching tool that may be mass-distributed, especially since the Oculus Rift hits the consumer market this year.

“It’s not intended in any way to be a replacement,” Sanders said. “What we can do, however, in the digital realm is augment what you see when you go and visit the real thing in ways you can’t do on site. It’s a way to supplement and expand the experience, not replace it.”

Optic-based technologies enable engineers to reassemble the past with such vividness, but as individuals and institutions increasingly embrace these methods to protect history and culture, we have to also think about the reliability of reproductions — what transformations occur when one progresses from an original artifact to an image to a software-created object. Artist and RISD professor Clement Valla introduces this discourse to The Missing through one of his draped foam sculptures based on an ancient vase in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s collection. From a 3D model of a krater, he has created a foam copy that replicates the original artifact’s shape and size, then blanketed that copy with linen on which he printed a flattened image of the 3D model. The result dances between sculpture and image, illuminating the various processes that constitute a reproduction and that ultimately favor and focus on surface appearances. Valla approaches digital reconstruction — “reverse archaeology,” as he called it — with a critical eye, acknowledging that while such efforts do salvage works, they may, just as excavations often do, introduce an unintended, largely unavoidable destruction of a different kind.

At a panel held in conjunction with the exhibit last week, one woman in the audience preceded her question with a request that Allahyari change the projected slide, which happened to be looping the clip of ISIS members trashing the Mosul Museum.

“I’m going to have nightmares about it,” she said, and urged for “something more uplifting.”

When we watch these terrorist-released videos, our immediate response may be to feel disheartened and helpless in the face of such blatant violence. But as The Missing demonstrates, there are ways to resist those bent on breeding fear. Even if we cannot always repair and regain fragments of our physical world, we can at least attempt to piece together history — and do so with proper intention and awareness.

The Missing: Rebuilding the Past continues at John Jay College’s Shiva Gallery (899 10th Ave, Midtown, Manhattan) through February 5. The exhibition may also be viewed online.