William R. Wilson is a Diné photographer who spent his formative years living in the Navajo Nation. Born in San Francisco in 1969, Wilson’s complex and nuanced oeuvre fully-developed while studying photography at The University of New Mexico (MFA, writing a dissertation on the photography of Milton S. Snow), as well as during his undergraduate studies at Oberlin College. In 2007, Wilson won the Native American Fine Art Fellowship from the Eiteljorg Museum and in 2010 was awarded a prestigious grant from the Joan Mitchell Foundation. Wilson is also an educator and has held visiting professorships at the Institute of American Indian Arts, Oberlin College, and the University of Arizona. Recently, Wilson managed The National Vision Project, a Ford Foundation funded initiative at the Museum of Contemporary Native Arts in Santa Fe, NM.

http://www.willwilson.photoshelter.com

Statement:

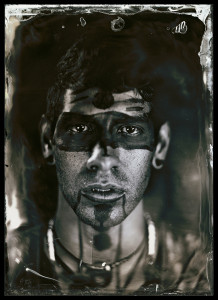

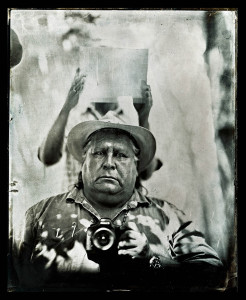

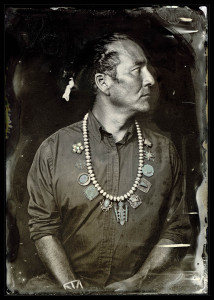

“As an indigenous artist working in the 21st century, I am impatient with the way that American culture remains enamored by one particular moment in a photographic exchange between Euro-American and Aboriginal American societies: the decades from 1907 to 1930, when photographer Edward S. Curtis produced The North American Indian.

With Critical Indigenous Photographic Exchange, I resume the documentary mission of Curtis from the standpoint of a 21st century indigenous, trans-customary, cultural practitioner. I want to supplant Curtis’s Settler gaze with a contemporary vision of Native North America.

This body of photographic inquiry stimulates a critical dialogue and reflection around the historical and contemporary “photographic exchange” as it pertains to Native Americans. By convening with indigenous artists, arts professionals, and tribal governance to engage in the performative ritual that is the studio portrait, the experience is intensified and refined by the use of large format wet plate collodion studio photography. This beautifully alchemic photographic process dramatically contributed to our collective understanding of Native American people and, in so doing, our American identity. In a gesture of reciprocity, the sitter receives the tintype photograph produced during our meeting, in exchange for a high-resolution scan of their portrait and a non-exclusive right to use it.

Ultimately, I want to ensure that the subjects of my photographs are participating in the re-inscription of their customs and values in a way that will lead to a more equal distribution of power and influence in the cultural conversation. It is my hope that these Native American photographs will represent an intervention within the contentious and competing visual languages that form today’s photographic canon.”

William R. Wilson