Marcelo Cidade was born in 1979 in São Paulo, where he currently lives and works. He is graduated in Fine Arts by Fundação Armando Alvares Penteado (FAAP). In São Paulo, Cidade creates works that express complex social conflicts and bring signs and situations from the street into spaces given over to art. One of his particular interests is the public space generated in urban areas and the technological flux of our surveillance society. A selection of Cidade’s solo shows are: Kadist Art Foundation, San Francisco (2014); Galleria Continua, San Gimignano, Italy (2015, 2014); Casa França-Brasil, Rio de Janeiro (2013); Galeria Vermelho, São Paulo (2012, 2010, 2008, and 2006); Furini Arte Contemporanea, Rome (2010); and Centro Cultural São Paulo (CCSP) (2008); among others. He has participated in group exhibitions at the Museo Tamayo, Mexico City (2014); Wexner Center for the Arts, Columbus, Ohio (2014); Museu de Arte do Rio (MAR), Rio de Janeiro (2014); Museo de Arte Moderna de São Paulo (2014, 2012, 2011, and 2010); the Broad Art Museum, East Lansing, Michigan (2013); the Krannert Art Museum, Champaign, Illinois (2103); CCA Wattis Institute for Contemporary Arts (2012); Tate Liverpool, England (2011); MUSAC – Castilla y Léon, Spain (2010); and the 27th São Paulo Biennial (2006); among others. Cidade has works in important public collections, such as Fundação Serralves, Porto, Portugal; Museu de Arte Moderna de São Paulo (MAM SP), São Paulo, Brazil; Museu de Arte de São Paulo (MASP), São Paulo, Brazil; Tate Modern, London, England; Kadist Art Foundation, France; Museo Tamayo Arte Contemporaneo, Mexico City, Mexico; Bronx Museum, New York, USA.

http://www.galeriavermelho.com.br/en/artista/47/marcelo-cidade

Felipe Scovino interviews Marcelo Cidade

Scovino: One of the features of your work is bringing to the field of art the debate around issues that artists are usually reluctant to approach. I’m basically talking about two aspects: political ideology and crime. Under the first one, you have Esquerda e Direita (2007) [Left and Right], which shows us that there is in fact no division between the two ideological systems. A number of your works deal with crime, including Eu-Horizonte 4 (2000) [I Horizon 4]. So I’d like to start our conversation by asking you to comment on these two themes: how do you see the relationship between art and crime in your work? And how do you approach the issue of political ideologies?

Cidade: In terms of the relationship with a certain type of political ideology, I’m somewhat surprised by the use of the term ‘ideology’. I don’t actually like the word because I think ideology perhaps means a political structure that existed only before the fall of the Berlin Wall, when situations were determined by the idea of left or right or Capitalism versus Communism. Today, it’s complicated to say what political ideology exactly is, because we live in a time where left and right are in many ways intertwined; they blend together and only the market brings a resolution. In Esquerda e Direita, I use a Siamese supermarket trolley where both sides are practically the same, but they still refer to the symbol of consumerism. The spectator can open or close it, deciding to fully close or open the market, and the left and the right can fit inside. My work’s political stance stems from the idea I had about being apolitical. In the 1990s and early 2000s I had an anarchic sort of lifestyle – skateboarding, listening to rap, etc. – always staying away from militant political motivations, such as my generation’s ‘caras pintadas’[1], a bunch of teenagers in Brasília doing some hippie protest. I ended up with an aversion to party politics. But over time, I realised that this a-partisanship or a-politics could also be a political position in the context of Eu-Horizonte, when for the first time I managed to join the experimentalism of a performance and the ‘illegal’ (but not crime, as being naked on the streets is only against morals and good manners). The idea was to break with uniformity, which is the city’s verticality, creating the horizon with my own body. Horizon as a metaphor for hope: the horizon we never reach with our own bodies. Going back to the question, the relationship between art and crime has always been an important theme to me, as I’m interested in using the urban or public level in an anarchical way, exploring these spaces differently from what is considered normal. This is the basis of invading trains and metro lines and of illegal tagging (when I say illegal I mean without asking permission). This opened me up to the idea of freedom. Moving away from social standards to reveal this type of freedom in a public space, in another space.

S: Following on from the previous question, another image that is always present in your work – more specifically in your participation at the 27th São Paulo Biennial – is the museum, or metaphorically society, under a state of siege. When you allegorically set up CCTV cameras (Direitos de imagem, 2006) [Image Rights] and built a line of bricks with broken glass (Intramuros, 2006) [Intrawalls], you brought a certain state of mind to inside the institution: the signs of violence, fear, crime, the curtailment of the right to come and go. The public space, the space of the museum, reflects the private space in a tragic, but most of all, real, way. In your work, the relationship between art and life takes place viscerally and cruelly. The space is filled with suspicion and detachment from other people. I’d like you to comment on how you built this image of a state of siege inside the São Paulo Biennial.

C: Suspicion is something I always bring to the fore, something that has always followed me as a lack of confidence not in the art field, but in Brazilian society as a whole, where everything that is public is destroyed. I come from the middle classes, which are greatly influenced by American culture and have a way of life totally based on a Capitalist hope, so my suspicion was always greater. I was raised in closed private condominiums and studied in private schools, using a private health service and other private services, always considering with suspicion and negativity everything that was public: public space, public education, public health. Today I have a little bit more awareness in terms of regaining these spaces and trying to understand their place in Brazilian society. Perhaps this position is more typical of São Paulo, as in Rio de Janeiro, for example, the idea of public space is broader than in São Paulo. I think that after the military dictatorship these public spaces started to shrink, giving way to privatisation under the idea of fear. The media nurtured the paranoia: the fear of using the public space, public schools, etc., as if public schools only attracted the ‘underclass’, public hospitals always had massive queues and the streets were full of criminals. Going back to the first question about ideology and the relationship with the notion of crime, I adopted this attitude through skateboarding, which took me to the public space and made me realise that fear was something very personal and that we can’t make generalisations. As for the Biennial, when I was invited, the curator Lisette Lagnado’s theme ‘How to live together?’ proposed a common space where the interaction between each one of the artists would generate a dialogue with Hélio Oiticica’s concept. However, at the same time, there is a certain innocence, a certain romanticism, in imagining this idea in an artistic environment such as the Biennial, where it is impossible not to see that it’s mostly a space of competition, of the market, and that artists are there to show their best so they can be accepted and appear in the media. Direitos de imagem are cardboard sculptures representing security cameras. They were somehow ephemeral, as the cameras fell and broke throughout the duration of the exhibition, and some were stolen by visitors. The idea was to show the fragility of a society of control. It also intended to force the spectator to look at the camera, to look for the object that was being called art, to invert the idea of surveillance, where the public watches the camera as the camera watches the public. One of the works you mentioned, Intramuros, also stems from the social displacement of the public arena. It deals with everyday control systems, which are created to deal with economic and social gaps. These systems include building dividing walls against burglars using the remains of consumption, such as broken bottles. This type of protection is much more democratic than the failed protection offered by the State. The work that was specifically developed for the Biennial, entitled Fogo amigo (Friendly Fire) was the most problematic one, as it imposed a discussion about living together. It established a relation between the attacks carried out by PCC – Brazil’s largest criminal organization, many of whose members are in prison – led and organized that week by the criminal Marcola from inside the prison, bringing São Paulo to a halt; and the fact that Edemar Cid Ferreira, President of the Biennial Foundation, was also in prison. The association between a criminal institution and an artistic institution, in this case the Biennial, relates to Foucault’s concept of ‘non-place’. The idea behind the work was to use the same mobile telephone signal-blocking device used in prisons. I was very curious about how it worked, so after some research I ended up finding the device. I ran a test and it worked within a 15-metre radius. My project for the Biennial was to install six blocking devices creating a sort of cold zone where mobile phones wouldn’t work. My intention was not to stop communication but to create a new human communication where people would have to find each other through moving, and would have time to appreciate the artworks in the museum, breaking with the mobile phone’s non-personal convenience. The project was censored. I received a letter from the institution saying that I would be going against people’s right to communicate. After negotiating with the curatorial team, I reduced the size of the project to one single blocking device, limiting its reach to a 15-metre radius. Over time, I realized that in fact the telecom company Claro was sponsoring the Biennial so it wasn’t fair play. I didn’t want my original project to be completely destroyed, so I devised a system in which I placed a blocking device inside backpacks, improvising with motorcycle batteries. On the opening day, five friends took the backpack inside the venue to block the whole mobile telephone system. It was clear that people were trying to find each other with their phones, as they would normally do in an event such as the São Paulo Biennial, and nobody knew what was going on, because there was no coverage. It was only when journalist Camila Molina of the newspaper Estado de S. Paulo wrote an article about it that the action became public. However, throughout the duration of the Biennial, some people noticed that even when they were very close to the blocking device, their phones still worked. I later found out that the Biennial’s fire department turned the device off every day as it was interfering with their radio communication. The work ended up being a discussion about the boycott. Perhaps the idea of ‘how to live together’ is in fact a massive problem because it might be too utopic to consider putting people that don’t know each other together. The Biennial proposed a discussion that was interrupted. The only place for the work was that specific situation, as nowadays the technology around mobile communication has already moved on and the way in which the PCC and institutions operate is also very different; therefore the intervention in that Biennial is somehow dated.

S: On the same theme, I’d like to ask a question about the São Paulo Biennial and censorship. In the subsequent edition, which became known as ‘The Void’ (28th edition, in 2008), a group entered the venue and tagged one of the walls. Caroline Pivetta da Mota ended up being arrested as a scapegoat. But in the next edition the taggers were invited to participate in the show. What do you think of that?

C: In my opinion, an illegal action is an illegal action, independently of its aesthetical form – it doesn’t matter if it’s a well-made drawing or only a tag. In Brazil, we have this idea of adopting foreign concepts without understanding them, creating expressions that don’t exist. The term ‘grafiteiro’ [a graffiti artist in Portuguese, whilst someone who tags is a ‘pixador’] is inaccurate as it comes from ‘graffiti writer’. To tag is to write; to write your name, and the aesthetic appeal is in the way the letters are written, and not in a drawing, cartoon or stencil. I think there is a mistake in the way the language is used to determine what’s acceptable and what’s not. Society is quick to differentiate between good and evil, so the ‘grafiteiro’ is the good guy because he draws nice clouds during the day with money from the Mayor, whilst the ‘pixador’ is the bad guy. There is a massive contradiction here as, in my opinion, if it’s illegal it’s all the same. In the specific case of the Biennial, this misunderstanding brought attention to a marginalised group. If an indigenous tribe had the opportunity to live inside the Biennial, they would walk around naked, shitting in the corner. They would do everything they would normally do and we, western white men, would judge them as wrong. This is exactly what happened: there was the opportunity to occupy the void. These people legitimately occupied it and the curators didn’t understand it, dismissing it as crime, something inacceptable and outrageous. Afterwards, two years later, as a sort of apology, the same people were invited in as a collective. This was the biggest mistake as, in the first place, there is no collective. Taggers are the most selfish people on the planet. They’re interested in becoming famous and they want their nametags to be well known and successful, and only they and a small number of people appreciate that. I think there’s a misunderstanding by thinking they are political heroes, engaged people that use tagging as a way of being anti-heroes. They use vandalism to highlight their own nametags; they want to prove they are the best, in a primate-like competition of imposing themselves on society. I believe in this type of action in the urban environment, but when the action is taken indoors it becomes interior design. Meanwhile, Damián Ortega worked with tagging on metal, and people think it’s beautiful. I’m interested in the double standard of what is and is not acceptable. There is a romantic idealisation of the artist, and a person is not necessarily an artist just by tagging.

S: I’d like you to comment on two particular artworks that are parodies of Brazilian art: Amor e ódio à Lygia Clark (2006) [Love and Hate Lygia Clark] and Transeconomia real (2007) [Real Transeconomy], alluding to photo records of two works by Cildo Meireles that usually appear on publications: Condensados 2 – Mutações geográficas: fronteiras Rio/São Paulo (1970) [Condensed 2 – Geographical Mutations: Rio/São Paulo Borders] and Cruzeiro do Sul (1969-70) [Southern Cross]. What was your intention with this research? In the case of Clark, you replaced her Hand Dialogue by a symbol of violence, of confrontation, of a power institution. There is no dialogue apart from mine; that is, the voice of the person who holds the authority. It is a structure of confrontation. In the case of Cildo, it seems to me that you have common interests such as global geopolitics, its crisis, authoritarianisms and questionable powers.

C: I like the connection you made with Clark’s Diálogo de mãos (1966) [Hand Dialogue] as perhaps I unconsciously made that relation, even if not directly. Amor e ódio à Lygia Clark stems from my perception of her Bichos (1960-64) [Creatures]. I saw these works for the first time at MAM São Paulo and each one of the objects was displayed inside a round glass so visitors weren’t allowed to interact with them, which was her idea in the first place. I fell in love with her work but also hated the misunderstanding of her idea. I chose the knuckleduster because I wanted to use a weapon used by hate groups. It has an urban and juvenile nature and there is a certain fetish around it, as you can’t buy it in shops. Some collections and fashion designers, such as Alexander McQueen, use it as an accessory, and so on. However, my proposition was to disrupt the fetish and remove the idea of violence by joining two knuckledusters, creating an object that brings two people together, in an attempt to force union through a hate object. Offsetting hate to create love. But I think it’s very interesting that you mentioned Transeconomia real in relation to Meireles because it’s actually an indirect reference. But this happens not only in those works. A number of my pieces start from there, when the use of references evolves and I know how to make it clear to whom I am referring. Besides the works you’ve already mentioned there’s also Lina Bo Bardi in Tempo suspenso de um estado provisório (2011) [Suspended Time of a Provisional State], in which I use her signature display racks with gunshots to allude to the institutional violence of dismissing her project. In some works I also approach Constructivism from São Paulo, such as in Coca com cola (2010) [which literally translates as ‘Coke with Glue’], in which I use the poem Coca-cola Coca-cola, referring to cocaine and glue, using a homeless person’s blanket. We must understand the reason behind criminality, behind violence, behind all these daily occurrences of people being stabbed in Rio de Janeiro or policemen killing people in the favelas. I think that reducing the age of criminal responsibility to 16 years old is to legitimatise all this stupidity and to forget that the root cause is the deterioration of education and memory. I think that by re-appropriating these artists’ works I’m highlighting an art history that is not talked about, that is not identified as important by us, but by Europeans and North-Americans. What I’m doing is restating the importance of these artworks as concepts of social transformation. My work is then only a pretext, as those who get to know Marcelo Cidade also get to know Bardi, Meireles, etc., and they can then research it further. The appropriation is increasingly more interesting to me, and so is the use of historical facts to question our modernity, our history, and going a little bit further.

S: The scathing tone of, for instance, the two artworks mentioned in the previous question can already be seen in Fuzilamento (2002) [Shooting], when you stand still and naked, reading a list of past social revolutions whilst the audience throws cement at you. Your criticism is even more evident and precise for the fact that the reading recalls the procedures and tone used by Concrete poets. In a single artwork you bring together – with irony – several references (political, social, ideological and artistic). The serious tone of a discourse, of a poet or a statesperson that speaks before their citizens, is lost, booed at and destroyed. There is no hierarchy or verticality. Power is destroyed.

C: I think people throw the cement and don’t realise the aggression and violence behind it. Your point is very interesting, as I had never thought about Fuzilamento on those terms. I have been trying to map how each work can reference other works so I can collate a list of points of interest, of the aspects that have remained and the aspects that were lost in 15 years of research. I believe that the temporal appropriation and displacement of art history concepts or issues regarding the public or private space are aspects that I have maintained and that are still very interesting to me. How can I resist and intervene in certain situations that are presented to me both in terms of history and space? I like what you said because the relationship with appropriation and reference still wasn’t fully clear for me in Fuzilamento.

S: To a certain extent, Brazilian art has followed a path of approaching violence as a departure point and topic of debate, such as in the works of Antonio Dias, Antonio Manuel, Artur Barrio, Carlos Zilio and Carmela Gross, created during the dictatorship. In the beginning of the 1980s, the interventions by 3Nós3, and more recently, by artists of the same generation, such as Alexandre Vogler, Andre Komatsu, Guga Ferraz, Ronald Duarte and a number of collectives – lots of them based in São Paulo, such as Frente 3 de Fevereiro and Bijari, to name but a few – discussed or have been discussing the tenuous relation that can exist between art and crime. I’d like to know which events – that may not necessarily be related to art – motivate you.

C: Every time someone asks me this type of question my memory breaks down [laughs]. But I can say that the way we discuss violence is very different nowadays. The theme of violence has gone through a total transformation in the past 40 years, since the 1970s. During the dictatorship, when freedom of expression was non-existent, people had to use different tools to talk about violence, in an indirect way, using allegory as critic, using different mediums such as poetry. Many musicians used metaphor to speak critically. This always troubled me: the way in which the metaphor becomes a surrealist text, as people can’t understand it when they don’t have the necessary historical knowledge. For a long time I didn’t enjoy this type of music as I didn’t get the preciousness of the metaphor. Today I realise I didn’t understand the correlations and the points that were being made, but now I find it amazing. But I think there is an issue here, because if I didn’t understand, lots of people didn’t understand it either. Therefore, I try to use my artwork – and I think this is also noticeable with other artists of my generation – to make more direct criticism. It’s a much more punk-rock attitude: going straight to the point without creating metaphors about possible change. Perhaps this is because we are a generation that suffered President Collor, that went through radical economic changes, that saw their family being harmed for various reasons. Therefore, we want immediate change, through street protest, through tagging, and we use creativity to achieve change. Aside from that, violence has also become more extreme in other aspects. I think the needs are more urgent: that’s why my generation, and all these different groups, went out onto the streets to carry out actions and interventions that are more radical, such as 3Nós3, which is perhaps the most radical group. I lost track of what I was trying to say…

S: I asked about things that motivate you, your references to visual arts, books, films, songs…

C: I’m motivated by pursuing what it means to be free today. What motivates someone to climb a building, risking his or her own life, to tag a name up there? What about Artur Barrio’s work in 4 dias….. 4 noites…….. (1970) [4 Days… 4 Nights…] in which he spends four days and four nights without eating anything just because he believes in something? We can think about many artists, and many people who are not necessarily artists but who believe in what they are doing. I really like Joseph Beuys’ concept that we are all artists, destroying the hierarchical, pyramidal chain, in which the artist is the most important person. Beuys places everything in the same horizontal plane, where everybody is an artist; therefore no one is. Currently, I’m mostly fascinated by the idea of ethics and freedom in things being produced – art or not art – that is, people that are fulfilled by their own work, regardless if they are artists or not. And there’s always a young artist or a new artist of an older age. And meeting people who believe in what they do is the most beautiful thing in the world, regardless of the art market, the art scene, or art itself.

S: Partly due to an art historiography that had to review its own concepts, the generations following Concrete and Neo-Concrete are often considered as inheriting, to a greater or lesser extent, a constructivist tradition and an aesthetic of fragility. How do you place yourself in this context? I see the way in which you deal with, for example, the ordinary, under a new notion of object promoted by these aesthetic languages. In Transestatal (2006) [Trans-state], debris is the material but also much more. You use a strategy of incorporating ‘elements that shouldn’t be there, that shouldn’t be called art’. How do you operate this transition from mistake to invention, from error to ‘erudite’?

C: I think there are some issues here. The problem is the stigma of what Brazilian art is. This is a weight on the shoulders of the artist who tries to understand and repeat a certain formula that has already been accepted, without looking critically at, or challenging this heritage. For example, in terms of fragility, what would it mean to use today a concept of thirty years ago without contextualising it in a social parameter? The greatest importance of the ordinary is to think that Capitalist society still generates consumption and that the resulting rubbish, the social residue, is not acceptable. The artist tries to question what is acceptable and what is not. Perhaps appropriating strategies that have already been eroded is a political stance. However, activating rubbish through reconstruction is to challenge what is accepted or not as art nowadays. I’m interested in the unacceptable perhaps because I live a life that is not accepted. I am free and I don’t have a typical socially-accepted working status. Most Brazilian men wake up at 6 am, go to work, and are married, with two kids and are Christian. When you say you are an artist, an atheist and single, people immediately look at you with suspicion and say: ‘he’s a bum, a tramp, doesn’t work’. This is still happening now! Therefore, when people ask ‘what do you do?’ and you answer: ‘I collect little stones and I dig up rubbish to make a bridge’, this is totally unacceptable. It’s socially absurd to make a living selling those things. People are outraged: ‘did you sell that rubbish to the museum of modern art?’ We still live in a conservative society. Perhaps there is a façade and things seem hype and modern, but when you show a piece of art using a homeless person’s blanket, people don’t understand and become suspicious – but they’ll nonetheless buy it without understanding what it is. For me, it is very important to deal with materials that come from a social world of exclusion, making the rich consume the poor, trying to invert the economic scale. After all, as Beuys said: ‘kunst is like capital’, and we can never change that. So how can we subvert a Capitalist system? Perhaps by adding value to things that have no value. In this sense, I’m attracted to the ordinary, in an attempt to subvert the idea of Capitalism.

[1] Translator’s note: In 1992 thousands of students protested on the streets against corruption involving President Fernando Collor. They became known as ‘caras pintadas’ – painted faces – as their faces were often painted in green and yellow, the colours of the Brazilian flag.

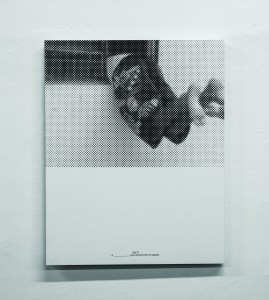

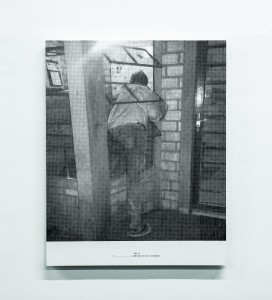

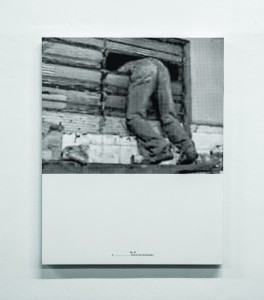

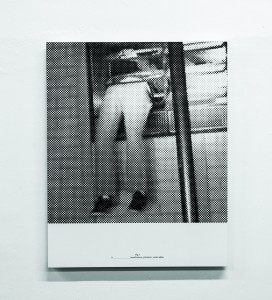

“A___________ social” series (2015)

Serigraphy over wooden board, acrylic paint, images from internet

Edition: 2/5

75 x 60 cm

Courtesy of Galeria Vermelho, São Paulo